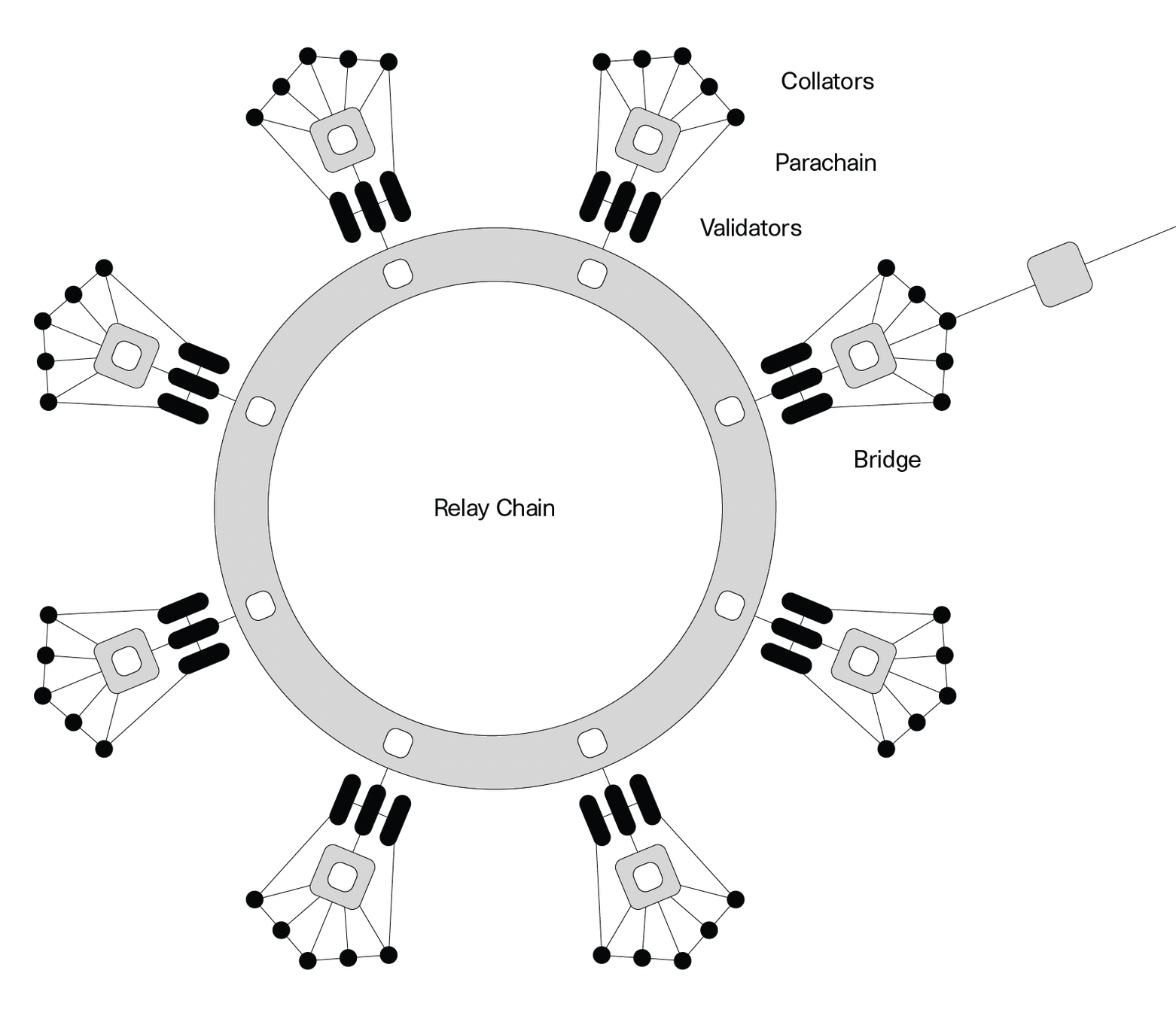

This post is about the technology powering Polkadot. Polkadot is a sharded blockchain with heterogeneous shards. What sharding means in this context is splitting up the work that happens onto multiple sub-blockchains, known as parachains. What heterogeneous means in this context is that each blockchain has its own state-transition function that is purpose-built for a specific use-case. Different types of transactions will have different homes, which allows for specialized chains to serve their users most efficiently. Polkadot provides security and messaging functionality for all attached parachains.

This post is primarily written for a technical audience with some knowledge of blockchain consensus. I hope it proves useful for people beyond that audience and provides insight into the problems and challenges facing base layer blockchains and how Polkadot approaches these problems. I'm not going to go through every nuance of our solutions, but I will give a deep description of the types of things we consider and how we provide the guarantees we aim to.

The chains before the chain

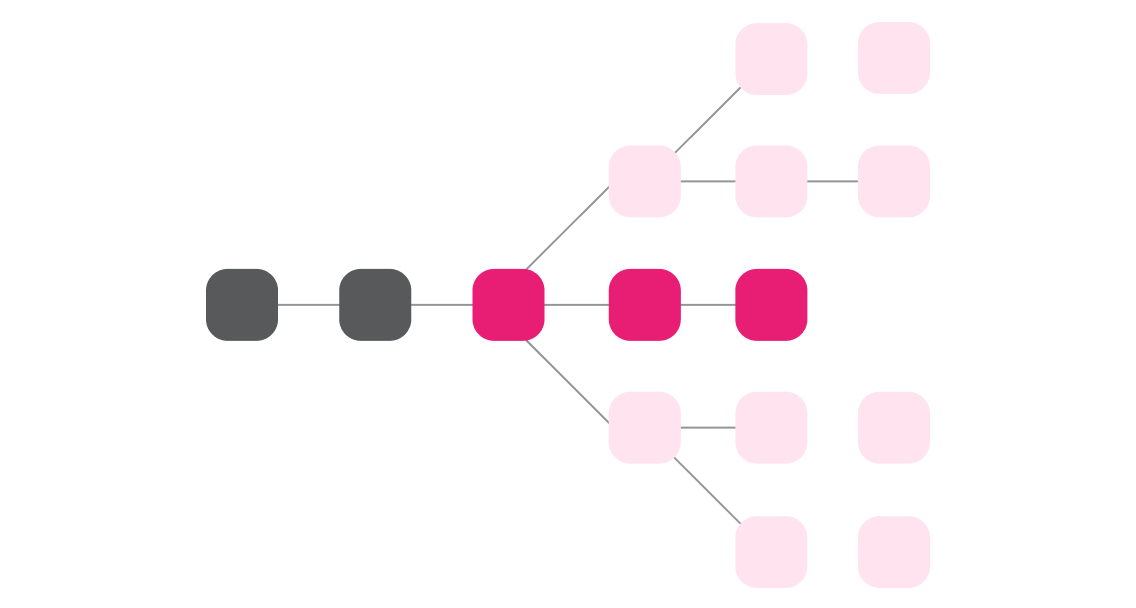

A simplified understanding of the blockchain involves only a single chain, extending from the genesis to the head of the chain. For many people, this is the only concept of the chain that matters - it represents all of the state transitions that have occurred and have been agreed upon by the network. The end goal of any blockchain consensus system is to provide observers with this source of truth. However, this single chain, that we can refer to as the finalized or canonical chain, is only the last remaining survivor of many possible competing chains that could have existed. The role of the blockchain’s consensus algorithm is to begin with many possible chains and ultimately finalize only one of them.

Block authors compete for the right to produce the next block, but there can be more than one winner at a time. In proof of work, miners earn the right to author on top of a given block (roughly) by finding a way to produce a new block that hashes to a unique random number that falls below some difficult target. It may take a huge number of tries before a miner finds a block which satisfies this condition in a sufficiently competitive environment. For reference, the cumulative hashrate of the Bitcoin network at the time of writing is 162 Exahashes per second, meaning that Bitcoin miners in aggregate attempt 162 quintillion times per second to earn the right to contribute the next block, and the difficulty target is set so on average only one hash will be below the target every 10 minutes. Note that it is possible for multiple miners to, roughly simultaneously, find a solution, which introduces a small fork in the blockchain. Future miners will have to choose which of those blocks to mine on top of, which can cause the forks to lengthen. The rule is to follow the longest chain, and it gets progressively more difficult for an attacker starting from a past block to catch up to and overwhelm some longer chain. As such, a block that is deep enough into the longest chain may be considered probabilistically final.

The Ouroboros family of proof-of-stake protocols use cryptographic technology known as Verifiable Random Functions (VRFs) to simulate proof of work by dividing time into discrete slots and giving each validator out of a registered and staked set of validators (the validator set) the opportunity to produce one verifiable random value per time-slot, which, if below a threshold, serves as a credential to allow the validator to author a new block. As with proof of work, multiple validators may produce a value with their VRFs that fall below the threshold and simultaneously author blocks, leading to forks. Validators are disincentivized from introducing intentional forks, i.e. using their credential to author multiple blocks within the same slot, by slashing their on-chain stake. These protocols also provide probabilistic finality under the longest-chain fork choice rule.

Unlike miners in proof of work, validators in an Ouroboros-style network need only run one computation for the chance to author a block as opposed to the absurdly large numbers of hashes that miners have to do. This allows validators to spend most of their time on building a block with transactions and subsequently allows the blockchain to contain more valuable computation.

Polkadot’s relay chain uses a protocol called BABE, which is an evolution of Ouroboros Praos. The specific improvement that BABE has over Praos is that BABE avoids being dependent on centralized NTP servers for validators to be aware of the current time.

BABE Paper

BABE Explainer Post

BABE is forkful, with probabilistic finality

While probabilistic finality is fine, waiting for a block to reach a certain depth in the longest chain is an inefficient mechanism, as it is designed to accommodate an anticipated worst-case where the network is under a certain level of network strain and attack. It may be the case that the majority of the network already agrees on which blocks are part of the canonical chain. In fact, in almost all cases, the network will be able to agree on a block being canonical far before it reaches the minimum depth in the longest chain. For this, we introduce the concepts of a finality gadget and of absolute finality. A finality gadget is a secondary consensus protocol running on top of a probabilistically final blockchain that proves faster agreement on which blocks the network will consider final. These consensus protocols introduce a further economic security property: the finality gadget will never finalize 2 competing blocks without slashing at least 1/3+ of the total stake of the validator set.

Polkadot’s relay chain uses a finality gadget known as GRANDPA. It can achieve near-instantaneous finality on sub-chains of any particular length, and functions roughly by having validators repeatedly vote on the blocks that they perceive to be at the head of the longest chain. GRANDPA is currently functioning on the Polkadot and Kusama networks, and on Kusama, which has 900 validators at the time of writing, it can achieve finality on new blocks within 3 seconds.

GRANDPA Paper

GRANDPA Explainer Blog Post

Validators vote on the chain that they think is best, and the algorithm lets them agree on a common block to be finalized

The combination of BABE and GRANDPA allows Polkadot to optimistically grow the chain with input from only a single validator, which is fast, and finalize that in the background by getting sign-off from a supermajority of validators. This combination of properties means that under good network conditions, Polkadot achieves high-throughput and low latency, and under bad network conditions, the relay chain achieves high-throughput and high(er) latency, as GRANDPA will devolve to tracking the probabilistic finality of BABE.

Sharding: scaling by subset selection

Let’s return to sharding. The goal of sharding is to improve throughput by splitting work, in the form of transactions, across many chains known as shards. The shards are referenced by and secured by a top-level blockchain. In Polkadot the top-level blockchain is called the relay chain and the shards are parachains. Most of the data that appears on the relay chain are transactions that include references to new parachain blocks, which makes processing any fork of the relay chain itself cheap. Note that I make a distinction here between arbitrary forks of the relay chain and the finalized relay chain. Most of our work here is about ensuring that the finalized portion of the relay chain, which users will view as the canonical chain, only contains references to parachain blocks which are valid.

This diagram or similar ones are distributed widely over the internet. They show how validators are split into groups and assigned to parachains and get parachain block proposals from collators. In this post I have created visual explanations of many of the more nuanced concepts.

Sharding is only an improvement to scalability if each validator only needs to check some of the submitted parachain blocks, as opposed to all of them. If there were 10 parachains, and each validator had to check all blocks from all 10 chains, we might as well just put all of the transactions onto one blockchain and call it a day. The trick is to find a way for each validator to do as little verification work as possible while still maintaining economic security: that validators who advocate for bad parachain blocks are economically disincentivized from doing so. More concretely, it should be impossible for an adversarial group of validators to collude to get a bad parachain block included in the finalized relay chain before losing all of their stake to slashing. Validators, and indeed small subsets of validators, can collude to get bad parachain blocks referenced by unfinalized forks of the relay chain, but we guarantee that these forks are ignored before finality and the offenders are slashed.

Parachain blocks are finalized when a relay-chain block that references them is finalized

Parachain blocks are finalized when a relay-chain block that references them is finalized

Let’s set down some concrete assumptions about the adversary that we defend against:

- The adversary can control up to 1/3 of all validators, and can control all of these validators to behave exactly as desired.

- The adversary can view all network messages between honest validators and the validators it controls

- The adversary can DoS up to X% of the validators at any time, preventing them from sending or receiving messages.

- It takes a fixed delay before the adversary can begin to DoS any validator

I won't be setting down a formal security proof for the protocol in this post, but these constraints should provide insight into the types of attacks that we intend to defend against.

In fact, our base unit of parachain consensus isn't actually a parachain, but something that we call an availability core or core for short. These are something like CPU cores: they operate in parallel, and have work scheduled onto them in discrete time-slots. Each parachain has its own dedicated core, which means that it's always scheduled onto a particular core. However, we can also multiplex multiple chains onto a single core. The only difference is the scheduling algorithm.

Cores serve as an effective description of the throughput of the relay chain. Cores directly correspond to the amount of work validators need to do. Each core can handle up to one parachain block per each relay-chain block, at peak.

In any sharded blockchain system, where only some validators check each parachain block, data availability is a crucial component to make sure that the data necessary to check a parachain block can be recovered for the purposes of fraud detection. Availability cores are managed by the relay chain and track which parachain blocks are pending data availability. The main purpose of availability cores is as a scheduling primitive and to provide backpressure when data availability is slower than usual.

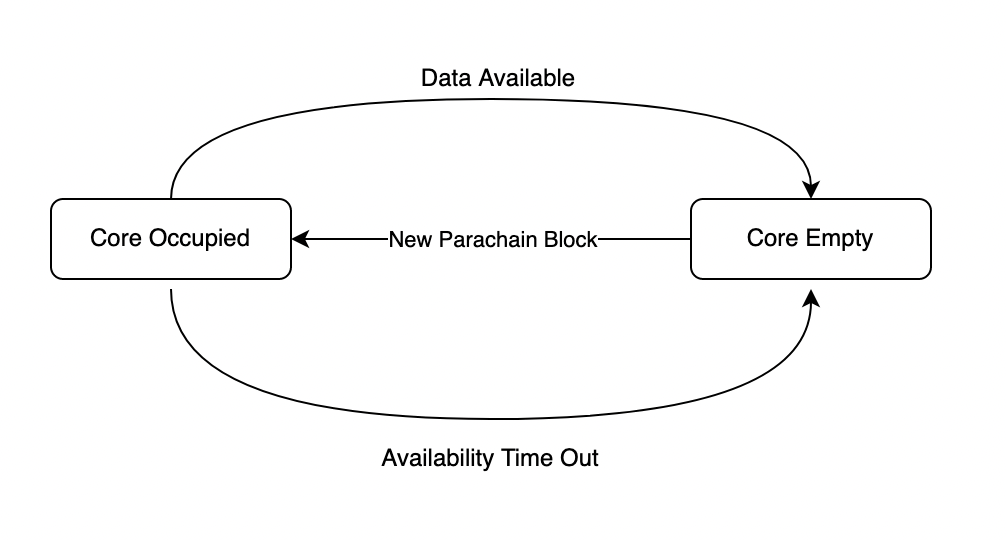

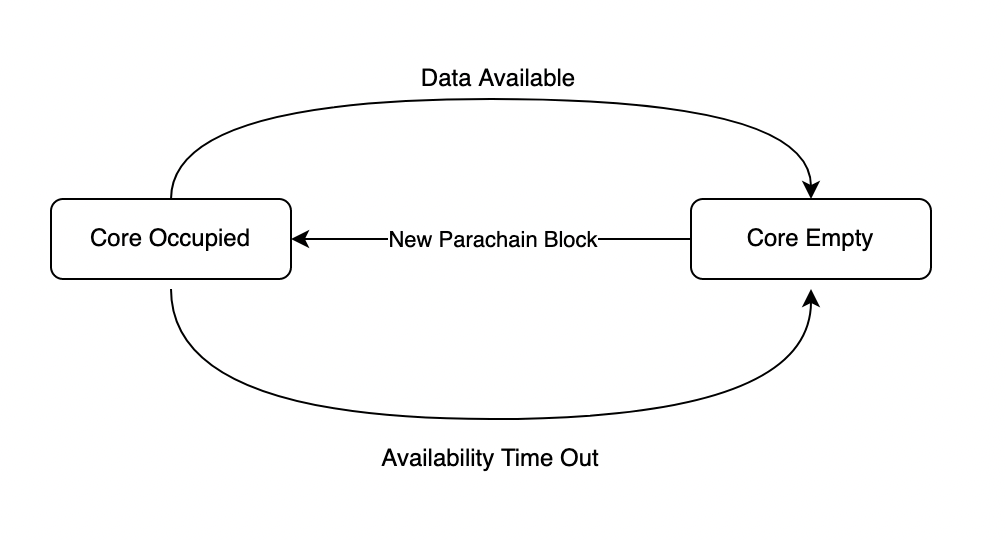

The logic of an availability core looks like this. Cores are empty when they're ready to accept a new parachain block, at which point they become occupied. Then, the data either becomes available or the availability process times out. At that point, the core becomes empty again.

It's helpful to divide parachain consensus up into 5 distinct protocols that are intertwined in relay-chain consensus.

1. Collation

2. Backing

3. Availability

4. Approval Checking

5. Disputes

Collation is the process by which parachain blocks are created. Collators build a parachain block and send it to validators.

Backing is the process by which parachain blocks are initially checked by a small group of relay-chain validators and registered on the relay chain. The main byproduct of backing is that it requires validators to put themselves at risk if the later protocols fail.

Availability is the process by which the backing validators distribute pieces of the data necessary to check the parachain block and ensure it is available to check later.

Approval Checking is the process by which random validators recover the data and execute the parachain block. They either approve or initiate a dispute based on whether they think the parachain block is valid.

Disputes are the process by which conflicting opinions by validators on a parachain block are resolved and bad parachain blocks are ignored and offenders punished. Disputes only exist as a failsafe and aren't expected to be triggered often.

Note that validators are likely to be engaging in each of these protocols at the same time, and often multiple instantiations of them. For example, a validator might be engaging in approval-voting for a parachain block that's further down the pipeline at the same time as it participates in backing for a newer block and disputes for an even older block.

This internal parallelism also reflects the architecture of the implementation: each of these protocols is implemented as an independent subsystem, and all the subsystems run in parallel. Every node is always doing a little bit of everything.

Submitting blocks and growing parachains

This section goes over how parachains grow in tandem with the relay chain.

Inclusion of a potential parachain block into a parachain takes 2 steps. The first is for the parachain block to be referenced by a relay-chain block along with attestations about its validity. The next step is for the corresponding data necessary to check the parachain block to be acknowledged as available in a subsequent relay-chain block.

Since the relay chain can have short-term forks, each parachain can also have short-term forks. If there are two competing relay-chain blocks A and B at a given height and A contains parachain block P and B contains parachain block P', then that also constitutes a fork in the parachain.

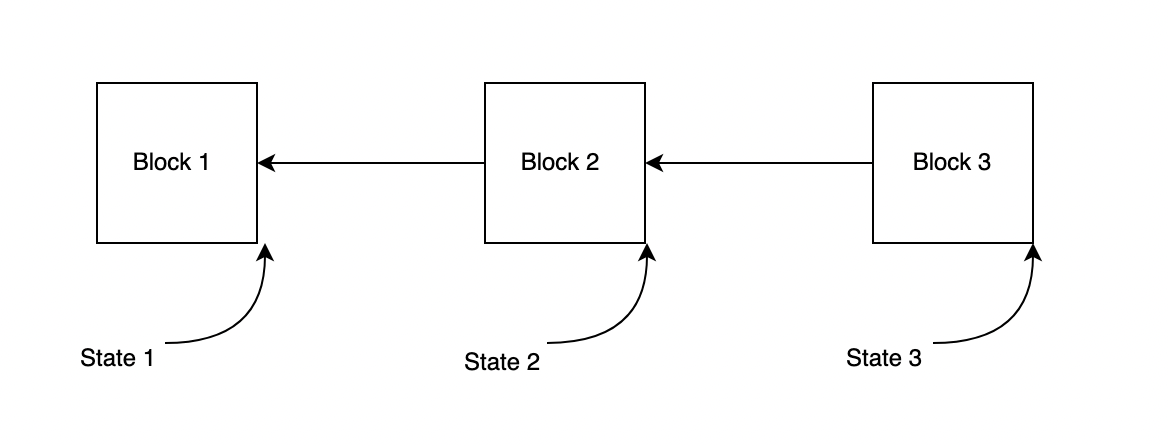

For the purposes of this post, we'll consider a simplified version of Polkadot's relay-chain state machine. As a reminder, each block in a branch of the relay chain represents a transition from the previous state to the next state.

Each block signifies an atomic unit of change from the previous state of the blockchain to some new state. Account balances, availability cores, governance proposals, and smart contracts are all examples of things that are part of the state of a blockchain. Blocks update the state either through inherent logic or transactions. Inherent logic refers to state updates that must happen even without transactions, as a result of the passage of time or the advancement of the block number.

When constructing a blockchain, the typical design pattern is for nodes to gather information and do work off-chain and then place a record of the work on-chain. As an example, you can view transaction inclusion through the same lens. Nodes participate in an off-chain gossip protocol to gather fresh transactions and then the block author bundles its choice of transactions together into a block. Parachains work the same way: most of the work is off-chain, but records of the work are preserved on the relay chain to provide a canonical indication of the consensus.

The off-chain work that nodes do to grow parachains involves collation, backing, and availability.

Nodes monitor the latest blocks of the relay chain to determine what work they should be doing.

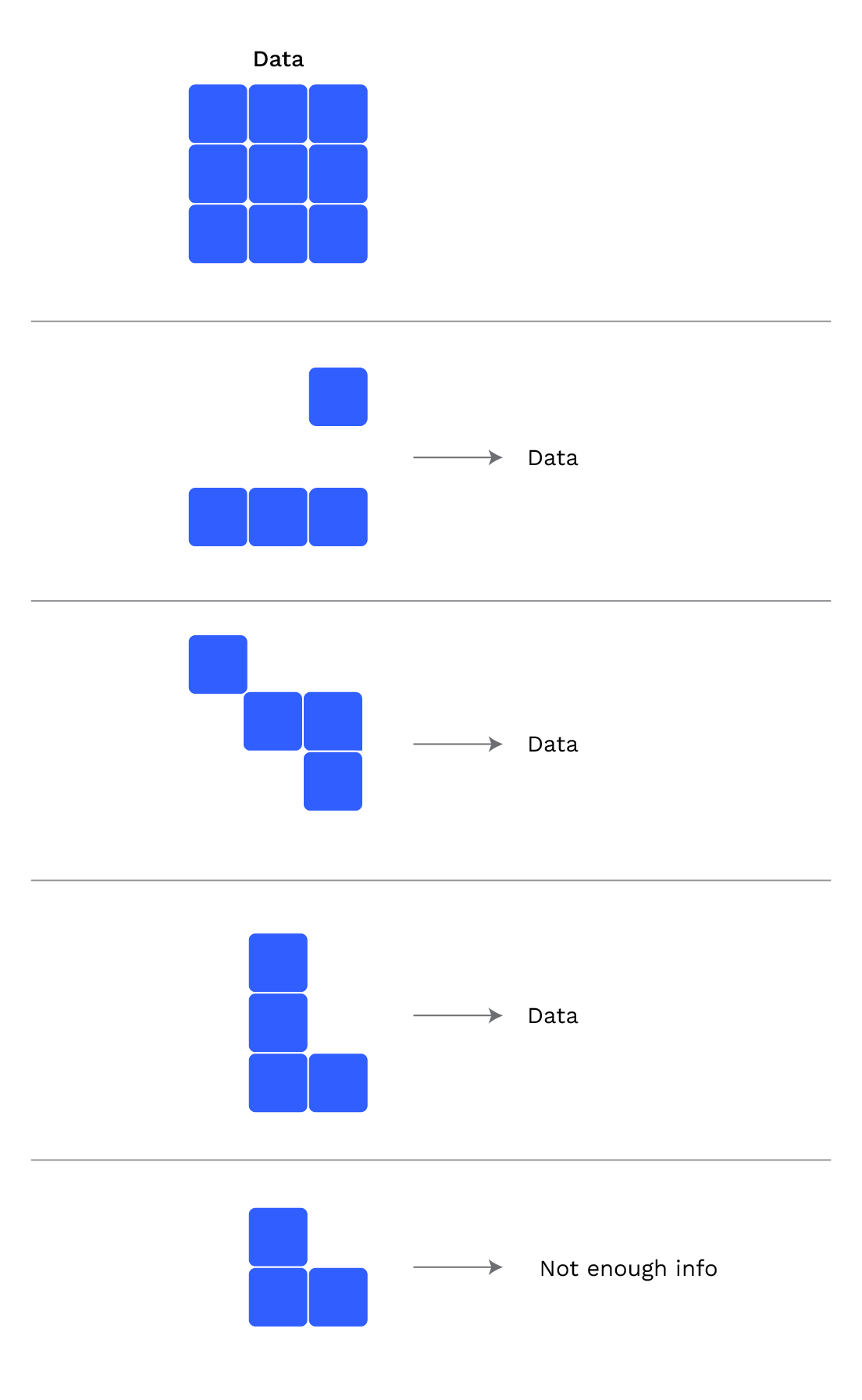

A collation consists of a parachain head and a PoV or proof of validity which is all data needed to check the transition from the previous parachain head to the current head. Only the heads make their way on chain, but the PoVs must be made available. We use erasure coding to ensure that PoVs are available: the data is split into pieces called chunks, one for each validator, and any large enough subset of chunks can recover the full data. This provides protection against nodes that go offline or lie about having their piece of the data.

In this example, data is split into 9 pieces and any subset of 4 or larger can recover the full data

When a validator observes that an availability core is empty and the parachain scheduled on that core is one that the node is assigned to, it'll attempt to gather a collation from a collator and participate in the backing process. New potential parachain blocks, along with their attestations by validators, are propagated through a gossip system. This means that every well-connected node is aware of every next potential parachain block. The next relay-chain block author monitors the network state and selects some set of new parachain blocks to be backed in the relay-chain block they author.

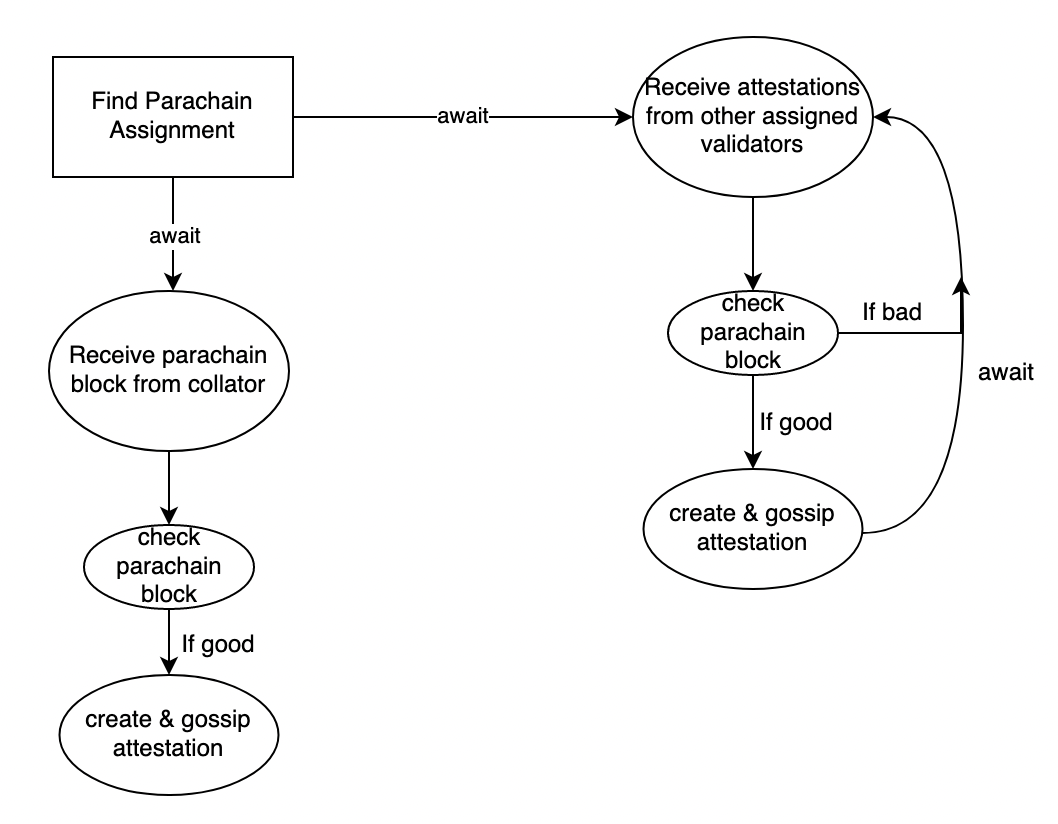

Here's a flowchart loosely describing the logic that validators perform for the backing process. They perform this logic whenever the availability core for the parachain is empty.

This diagram shows how validators get fresh parachain blocks from collators and collaborate with other validators to get enough support from the assigned validators. Validators who aren't assigned to the parachain still listen for the attestations because whichever validator ends up being the author of the relay-chain block needs to bundle up attested parachain blocks for several parachains and place them into the relay-chain block.

Once a parachain block is backed on chain (i.e. its header has appeared in a relay-chain block along with attestations by selected validators and it's passed various sanity checks) it begins occupying the availability core.

When a validator observes that an availability core is occupied, it attempts to fetch its chunk of the erasure-coded PoV if it was not part of the group of validators that initially attested to the block. Otherwise, the validator is responsible for distributing chunks to the corresponding validators.

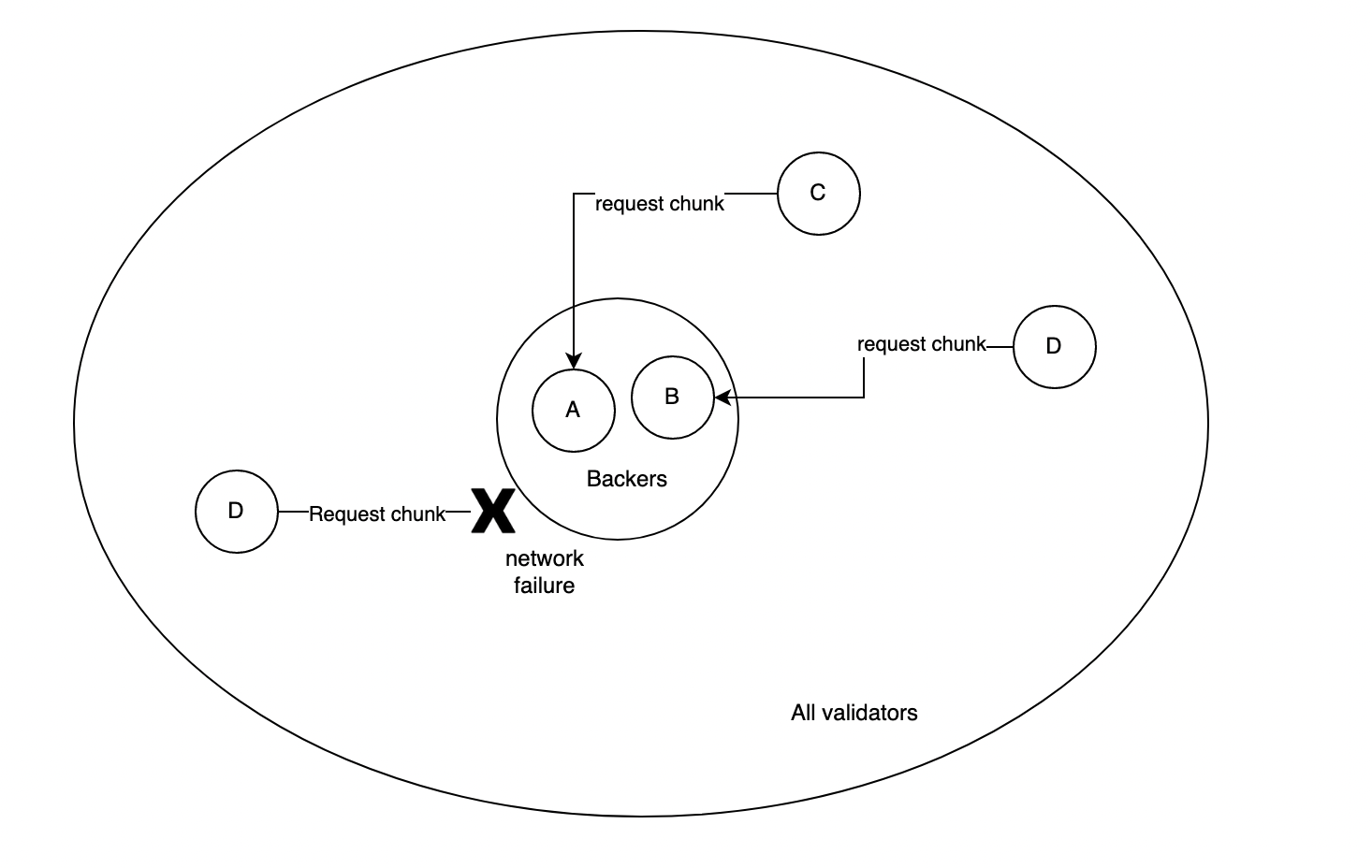

Availability distribution: non-backing validators request their chunks from the backing validators. Some of the non-backing validators might not be able to connect directly, but that's OK as long as enough are.

Validators request their chunks of data from the backing validators, who are required to distribute them

Every validator signs statements about which parachain blocks it has its chunks for and gossips those statements. The relay-chain block author includes such statements in the relay chain. Once 2/3+ of validators have indicated they have their chunk for the parachain block occupying a core, parachain block is considered available and is officially included as part of the parachain and the core is made free again.

If availability isn't achieved within some set amount of blocks, then the core is made free, having been considered as timed out and the parachain block occupying the core is abandoned.

Availability Core Logic as a recap

To sum up, the backing and availability protocols ensure that by the time a parachain block has been included, it's been attested to by a small handful of validators and the availability of the PoV needed to check the parachain block has been attested to by at least 2/3 of validators. Framed another way, backing and availability are about getting skin in the game and enforcing accountability. The next sections will discuss how Polkadot ensures that no parachain block gets finalized without being checked more thoroughly.

Approval checking and finality

Approval Checking is a mechanism by which validators randomly self-select to check parachain blocks that are available and communicate the intention and results of their checks to the rest of the network.

For now, let's leave the actual process of approval checking as a black box. We'll start by giving some background on what we want this protocol to do, so it's clear later on why it operates the way it does.

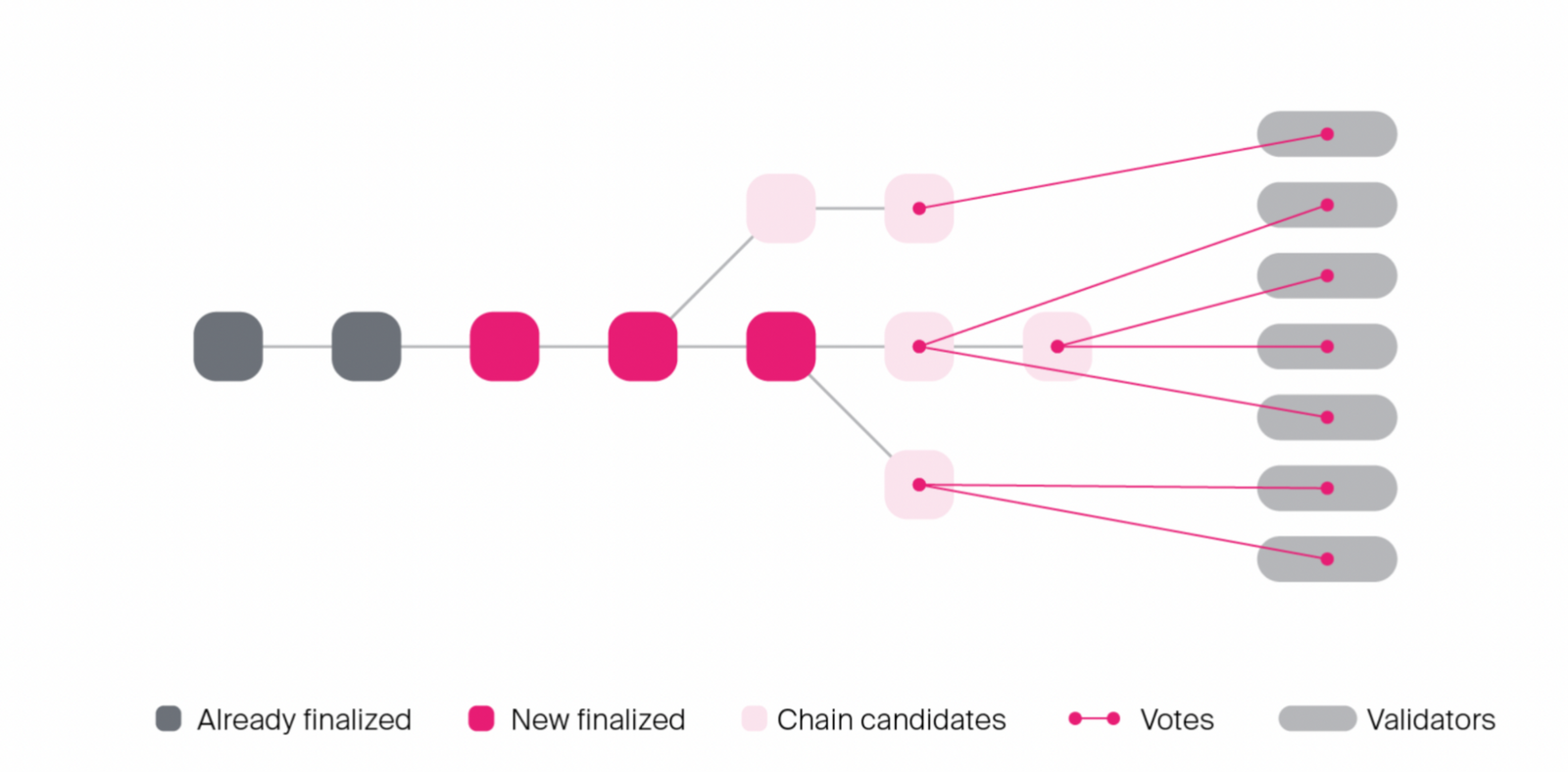

As we've already established, every validator node participates in GRANDPA, the finality gadget. GRANDPA proceeds in rounds, and we can view an over-simplified version of the work that each validator does in each GRANDPA round as the repetition of these steps:

- Next round begins

- Choose a finality target block: the best block we'd like to be finalized

- Cast a vote on the finality target

- Wait for other validators' votes

- Find the highest common block that appears in at least 2/3 of the chains voted on by validators

- Finalize that block

- Round ends

The only flexibility that a validator has in this process is in step 2: its choice of the block to vote upon as their finality target. This choice is known as the voting rule. In basic GRANDPA, each validator just chooses the longest branch of the relay chain they're aware of and submits the head of that chain as their vote. However, for parachain consensus we introduce a new voting rule.

The GRANDPA voting rule for approval-checking says that each validator should:

1. Choose the longest branch of the relay chain

2. Find the highest block B in the chain such that every block between the current finalized block and up to B only triggers inclusion for parachain blocks that the validator has observed to have been approved by enough validators.

Let's break this down. Remember that one main goal is for the network only to finalize parachain blocks that are actually good and also for every validator to do as little work as possible so the network can scale. So in parts:

- Find the highest block B in the chain: We want each node to vote on the highest possible block that fits the other criteria so finality advances as fast as possible.

- such that every block between the current finalized block and up to B: The voting rule needs validators to vote on a chain that only contains good parachain blocks. In GRANDPA, a vote on a block counts as a vote on all its ancestors, so even if block 100 contains only good parachain blocks, blocks 99 and 98 might not. Therefore the voting rule needs to find the highest contiguous chain of relay-chain blocks passing the other criteria.

- only triggers inclusion for parachain blocks: Referring back to the section on parachain extension, what this is talking about are the parachain blocks have become available by virtue of the availability attestations in the relay-chain block and that the parachain blocks have been added to the parachain. Parachain blocks that aren't yet available don't count as part of the parachain yet.

- that the validator has observed to have been approved by enough validators: What this refers to is the approval-checking mechanism we'll describe below, which is a way for validators to have high confidence that a parachain block is good without necessarily checking it themselves by relying on the checks of others.

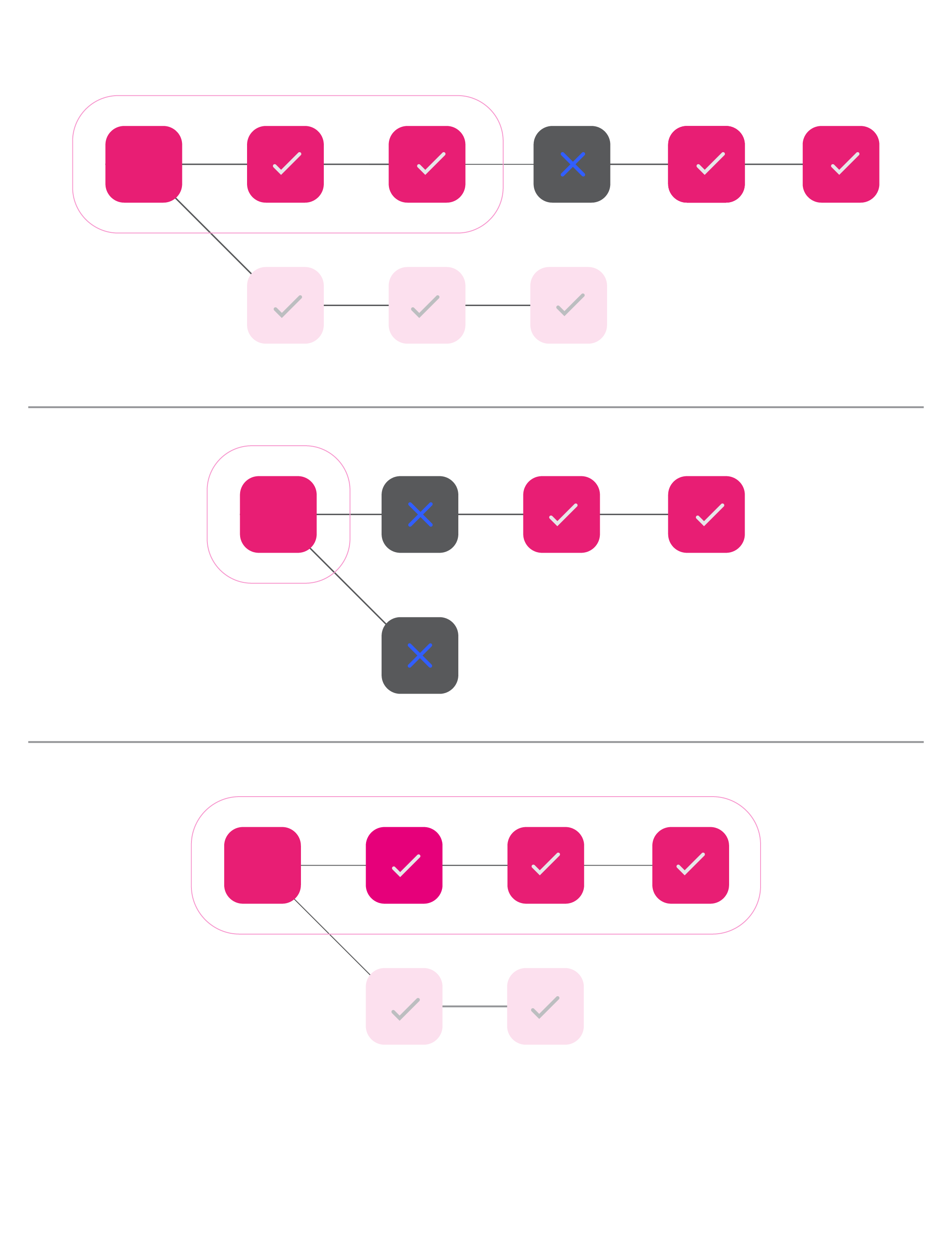

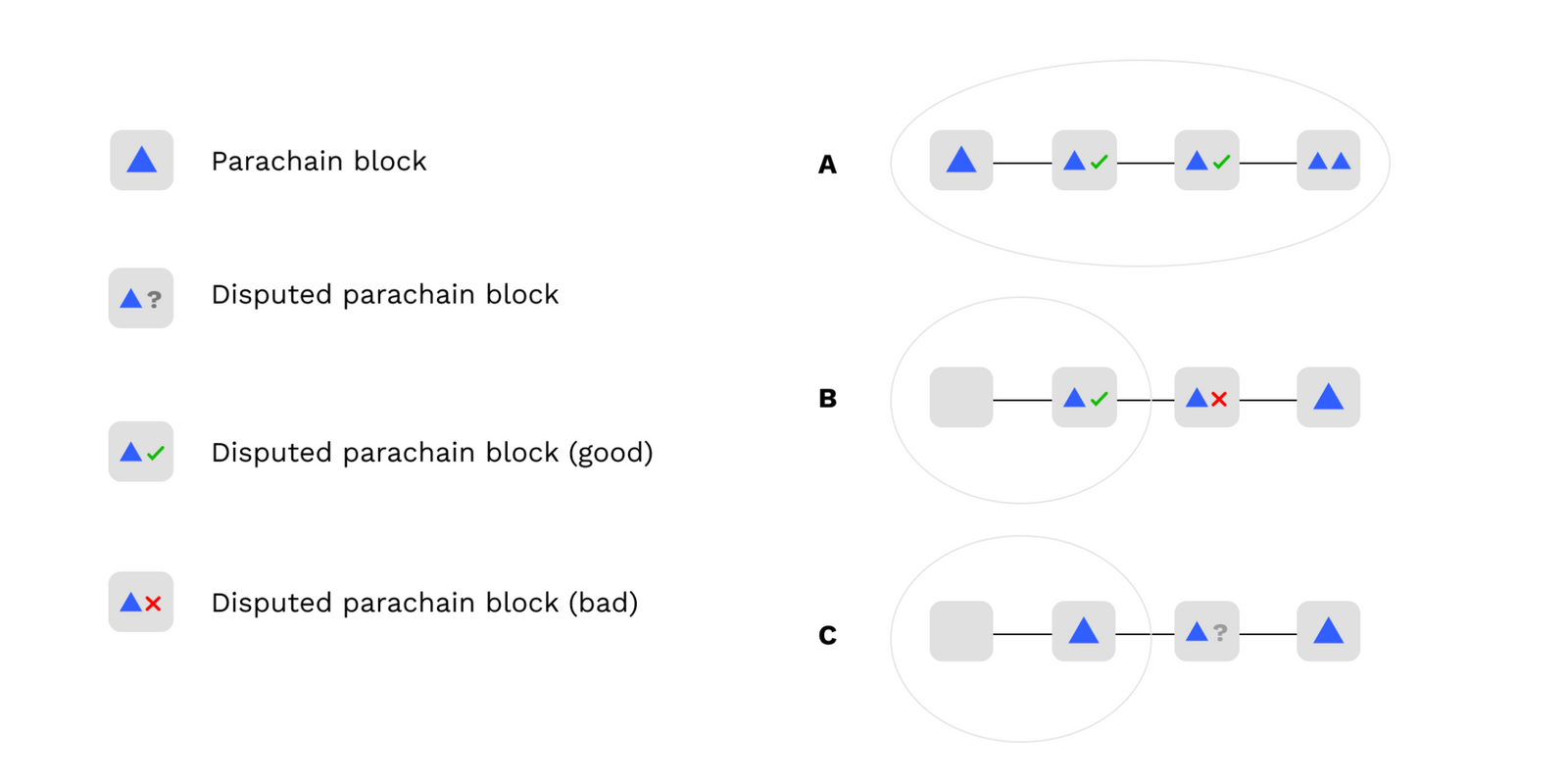

Below are 3 examples of how the voting rule is applied to select which blocks to vote for being finalized.

In the first example, this is showing the contiguity property as well as the fact that we choose an ancestor of the best chain.

In the second example, we vote on the finalized block because neither chain is finalizable.

In the third example, the entire best chain is finalizable so we choose to vote on that.

Lastly, it's worth noting that this voting rule is a process that runs on each validator and that they all may have different opinions on the finality target based on the relay-chain blocks and approval messages that they've seen. But this plays nicely into GRANDPA: if all honest validators run this voting rule, then no relay-chain block can get finalized unless it is agreed as finalizable by 2/3 of nodes.

Approval checking slows down finality a little, but only a little. Parachains are allowed to have around 3 seconds of execution time, and it takes around 1 second to recover the data and a few extra seconds for messages to be gossiped. In the optimistic case, this means that it adds around an extra 5 seconds to finality. And this is true finality, with the entire weight of the Polkadot behind it.

So let's go into the process of approval checking and what nodes are actually doing to get an idea of which parachain blocks are good and have been checked by enough validators.

Approval checking properties and security

Approval checking is a sub-protocol that validators run for every single parachain block.

Every validator node is running an approval checking process for every parachain block in every relay-chain block. This process has a few properties:

- The process on any particular node either outputs "good" or stalls.

- If the parachain block is valid (i.e. passes checks) then it will eventually output "good" on honest nodes.

- If the parachain block is invalid then it will only output "good" on honest nodes with low probability

Note that the "low probability" in the invalid case is something like 1 in several billion, depending on variables like the number of validators and the number of minimum checkers. This isn't the cryptographic version of low probability, but it is suitable for crypto-economics.

The security argument for Polkadot is based on Gambler’s Ruin. While it's true that an attacker who can take billions of attempts to brute-force the process would eventually be successful, we combine this process with a slashing system that ensures that each failed attempt is accompanied by a slash of the attacking validators' entire stake. Polkadot is a proof-of-stake network, and at the time of writing, each validator is backed by approximately 2 million DOT of stake. Most likely, each failed attempt would result in the slash of 10 or 20 validators. But even if only 1 validator gets slashed, it's still apparent that an attacker's funds would dry up quickly before success is likely.

We achieve this with a few other properties of approval checking:

- Validators' assignments to check a parachain block are secret until revealed by themselves.

- Validators' assignments are deterministically generated.

- Validators broadcast an intention to check a parachain block before recovering the data necessary to perform those checks.

- When validators broadcast an intention to check a parachain block and then disappear, this causes more honest validators to begin checking.

Property 1 ensures that an attacker doesn't know who to DoS to prevent them from checking a block.

Property 2 ensures that even if the attacker has gotten a lucky 'draw' and has enough malicious nodes to convince honest nodes that something has been checked, that there are most likely honest nodes that will do the checks alongside them, and those honest nodes will raise an alarm.

Property 3 ensures that honest nodes don't accidentally reveal themselves as checkers by requesting data from malicious nodes and then get taken offline by the adversary with nobody noticing. i.e. if the attacker tries to silence checkers it will be noticed by others.

Property 4 ensures that nodes that appear to have been DoSed will be replaced by even more nodes. Approval-checking is meant to be like the hydra: if you cut one head off, 2 more heads appear.

The next sections will go into more detail on how approval-checking actually works.

What do validators check?

The goal of validators here is to decide if the backing validators were involved in any misbehavior. This takes 3 steps:

- Download the PoV data to check the block. This is done by getting 1/3 of the chunks and combining them to form the full data.

- Ensure that the PoV data corresponds to a valid parachain state transition.

- Ensure that all the outputs committed to by the parachain block header actually match the outputs of parachain block execution.

Recovering availability should never fail under the assumption that >2/3 of nodes are honest and have committed to having their chunk of the data. This is why approval checking is only done for available parachain blocks.

However, steps (2) and (3) can both fail. When step (2) fails, it indicates that the state transition itself is garbage. When step (3) fails, it means that the state transition succeeded, but the information recorded on the relay chain about the outputs of the state transition was false.

One important case to note in step (3) is that the parachain block header contains a commitment to all the chunks of the erasure-coding. We have validators do an extra check after recovering the PoV data which is to convert the PoV back into its erasure-coded form and make sure that the commitment in the header matches all the chunks. If there's no match, this averts a type of attack where an attacker can selectively choose which validators can recover the data. The way the attack works is this: an attacker splits the data up into chunks and replaces all but 1/3 of the chunks with garbage. It distributes 1 valid chunk to an honest validator, and gives another 1/3 of validators garbage data. The malicious 1/3 of validators keep back the rest of the chunks with valid data. This means that there are enough validators (2/3 + 1) to consider the data available, but if the malicious validators refuse to answer requests about their 1/3 of good chunks, then only garbage will be available. Checking that the re-encoding of the data actually matches the commitment defeats this attack soundly.

If either steps (2) or (3) fail, the checker will raise a dispute and escalate the block to all validators to perform the same checks. We'll return to disputes later to discuss exactly what that means.

When to check

One of the key insights to understand the approval checking system is that every validator is assigned to check every parachain block, but it's a matter of when they check. If a validator sees a parachain block as approved before it's their time to check, then they simply don't check and they move on.

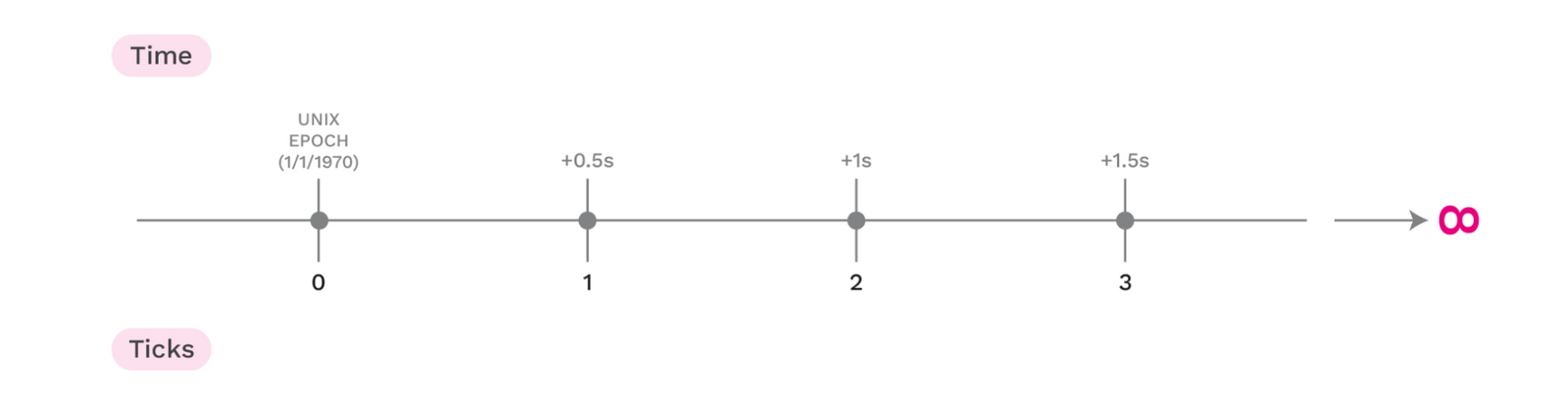

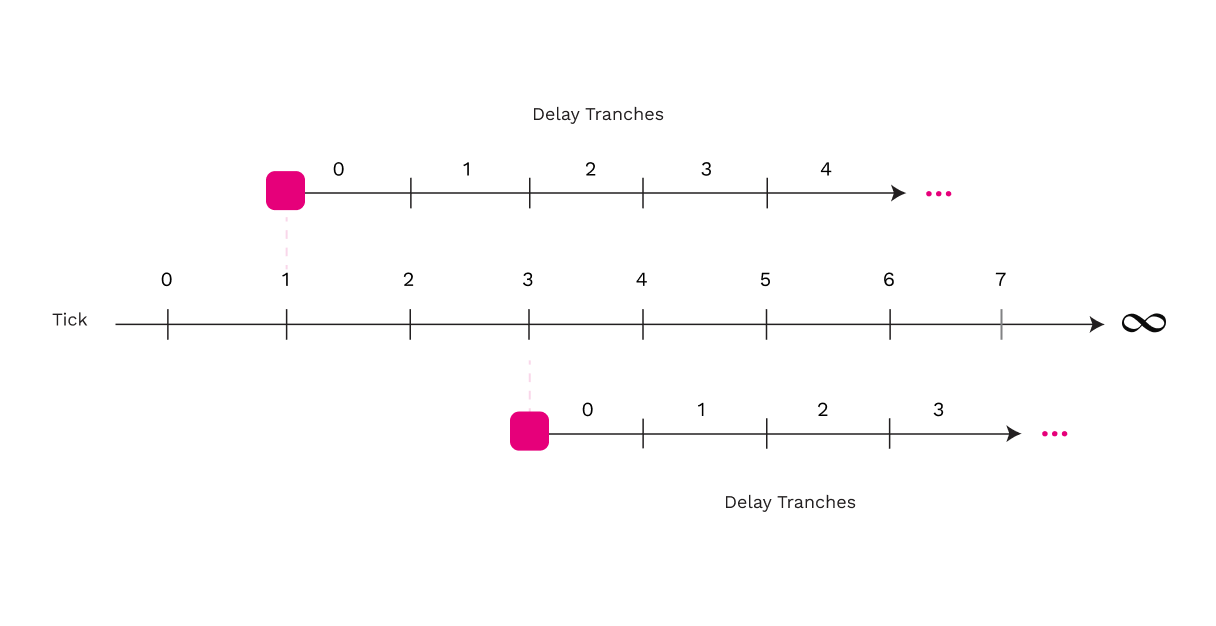

Time is divided into discrete ticks of 0.5 seconds starting from the Unix Epoch. The choice of 0.5 seconds is based on the expected time it takes for small messages to propagate through the gossip network.

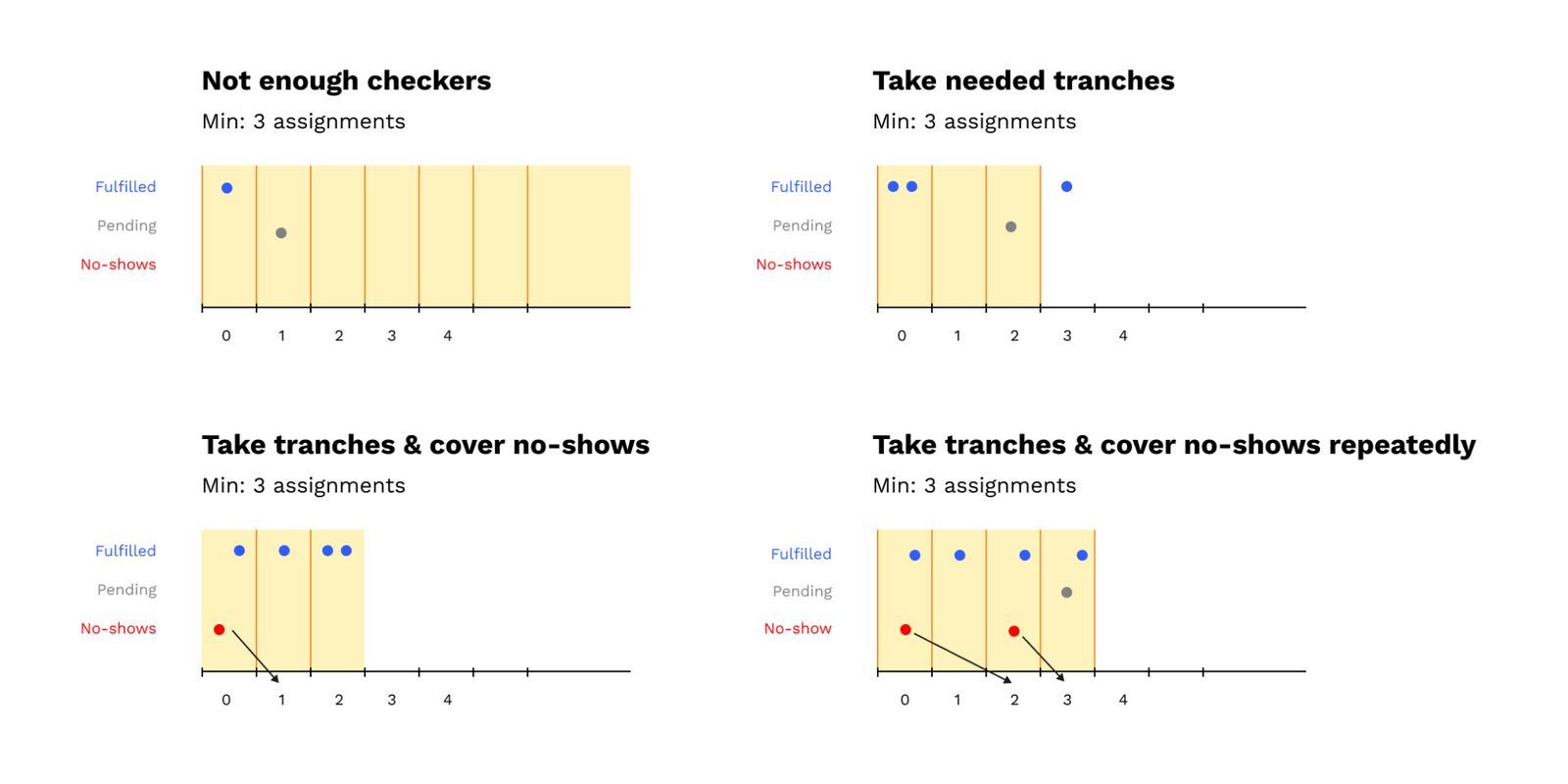

The time when a validator is intended to check a parachain block is expressed in a delay tranche, which is relative to the parachain block. Delay tranches range from 0 to MAX_TRANCHES, and correspond to the number of ticks after a node becomes aware of the parachain block becoming available. Nodes have slightly different views of which tick tranche 0 corresponds to. MAX_TRANCHES is a protocol parameter which determines how long it takes to check each parachain block. Setting it too small means that we may select more checkers than we need and thereby waste effort. Setting it too large means that it takes too long to check the parachain blocks. For reference, this parameter is set to 89 on Polkadot and Kusama at the time of writing.

Ticks are a discrete measurement from time, based on half-second increments starting from the Unix Epoch.

Delay tranches are offsets relative to the tick where a relay-chain block was produced.

Tranche 0 is special, in that the expected number of checkers in tranche 0 is designed to be roughly equal to MIN_CHECKERS, which is a protocol parameter that specifies the minimum amount of checks that are required before a parachain block can be considered approved by the approval checking procedure.

Validators who were part of the backing group for the parachain block aren't allowed to participate in approval checking because their checks would be redundant. All other validators run a VRF computation locally to determine in which delay tranche they're meant to check.

Assignments, approvals, and no-shows

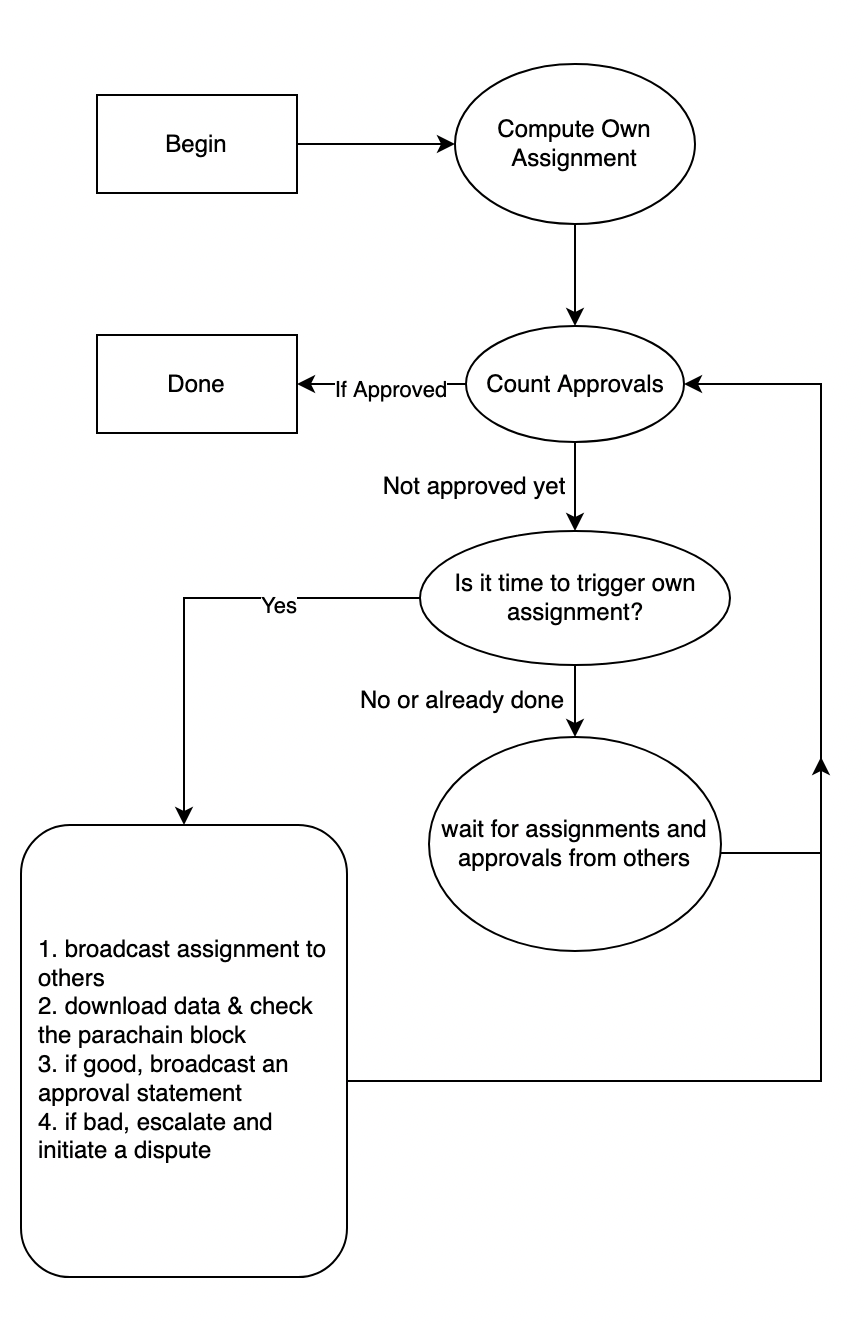

There are two kinds of messages validators send in approval-checking: Assignments and Approvals. Assignments are used to communicate intent and eligibility to check a parachain block, and an approval message indicates that a parachain block has passed all checks.

Every validator immediately generates an assignment to check the parachain block by using a VRF and the parachain ID and relay-chain block BABE credential as input. Validators keep their assignment private until it's needed. Each assignment is uniquely and deterministically associated with a delay tranche, which indicates the delay tranche when the validator is assigned to check the parachain block.

The VRF is important because it means that the assignment is verifiable by recipients and that the assigned validator has no influence over the delay tranche they're assigned to. Validators do have some indirect influence via more sophisticated attacks that involve deliberately forking the relay chain when the BABE randomness is favorable, but I'll save that for another article.

An approval is a simple message, signed by the issuing validator, that indicates that a parachain block has passed checks.

When a validator begins checking a parachain block, the first thing it does is gossip its assignment to other validators. This informs the other validators to wait for a corresponding approval message. Once the validator has finished checking, it issues an approval message. If the approval message doesn't come within NO_SHOW_DURATION, then the other nodes consider the initial validator to be a no-show. No-shows are intended to indicate that an adversary observed the validator's intention to check the parachain block and attempted to silence them. NO_SHOW_DURATION is a protocol parameter that is currently set to 12 seconds on Polkadot.

Here's a diagram showing 3 cases: a no-show, a fulfilled assignment, and a late fulfillment. The last case is especially important, because it shows how validators can 'come back from the dead' and have their approval count even after being considered a no-show.

Getting to yes: scheduling and the approval state machine

This last section on the approval checking protocol will detail the state machine for approval of a parachain block.

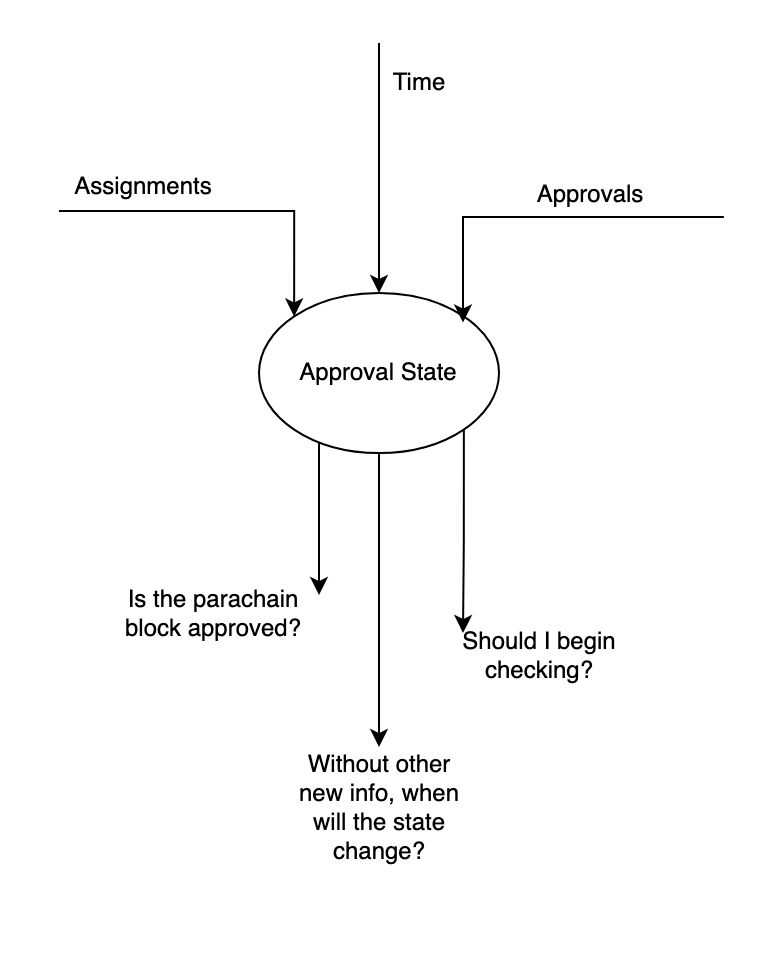

Every validator node maintains an approval state for each included (available) parachain block. Validators' versions of the state may differ due to timing and asynchrony in the network. The state lets us answer questions such as:

- Is the parachain block approved?

- Is an assignment with tranche T relevant?

- In the absence of other input, what is the next point in time where the answers to questions (1) or (2) might have changed?

The approval state can be updated in 3 ways: by receiving a new assignment, by receiving a new approval, or by the advancement of time.

Validators run the state machine until the answer to question (1) is 'yes'. After every piece of input, they use question (2) to determine whether they should begin checking the parachain block themselves, by seeing if their assignment is relevant. Question (3) is needed only for optimization purposes: nodes are typically running thousands of these state machines in parallel (one for each unfinalized parachain block) and it's inefficient to poll all of them every tick.

This is the logic each validator runs until parachain blocks are approved

What the state actually contains is 2 parts:

- All received assignments, ordered by tranche and annotated with the tick at which they were first observed.

- All received approvals.

A validator doesn't include its own assignment in the state until it begins checking. Upon producing an approval, a validator includes that in the state.

Here's a visual representation of the state; it's a neutral object which can answer questions based on which assignments have come in, how much time has passed, and which approvals have come in.

One of the most important operations on the approval state is figuring out which assignments to count. We take delay tranches in their entirety. Assignments are always bundled along with all other assignments from the same delay tranche. A node will never count one assignment from a delay tranche without counting all the other assignments from the same delay tranche that it's aware of.

An assignment is in one of 3 states:

- Pending: The assignment has no corresponding approval, but it was issued recently.

- Fulfilled: The assignment has a corresponding approval.

- No-show: The assignment has no corresponding approval and it was not issued recently.

No-show assignments need to be covered by at least one non-empty tranche. That is, each no-show needs to be covered by at least one assignment but in expectation more than one (based on parameterization).

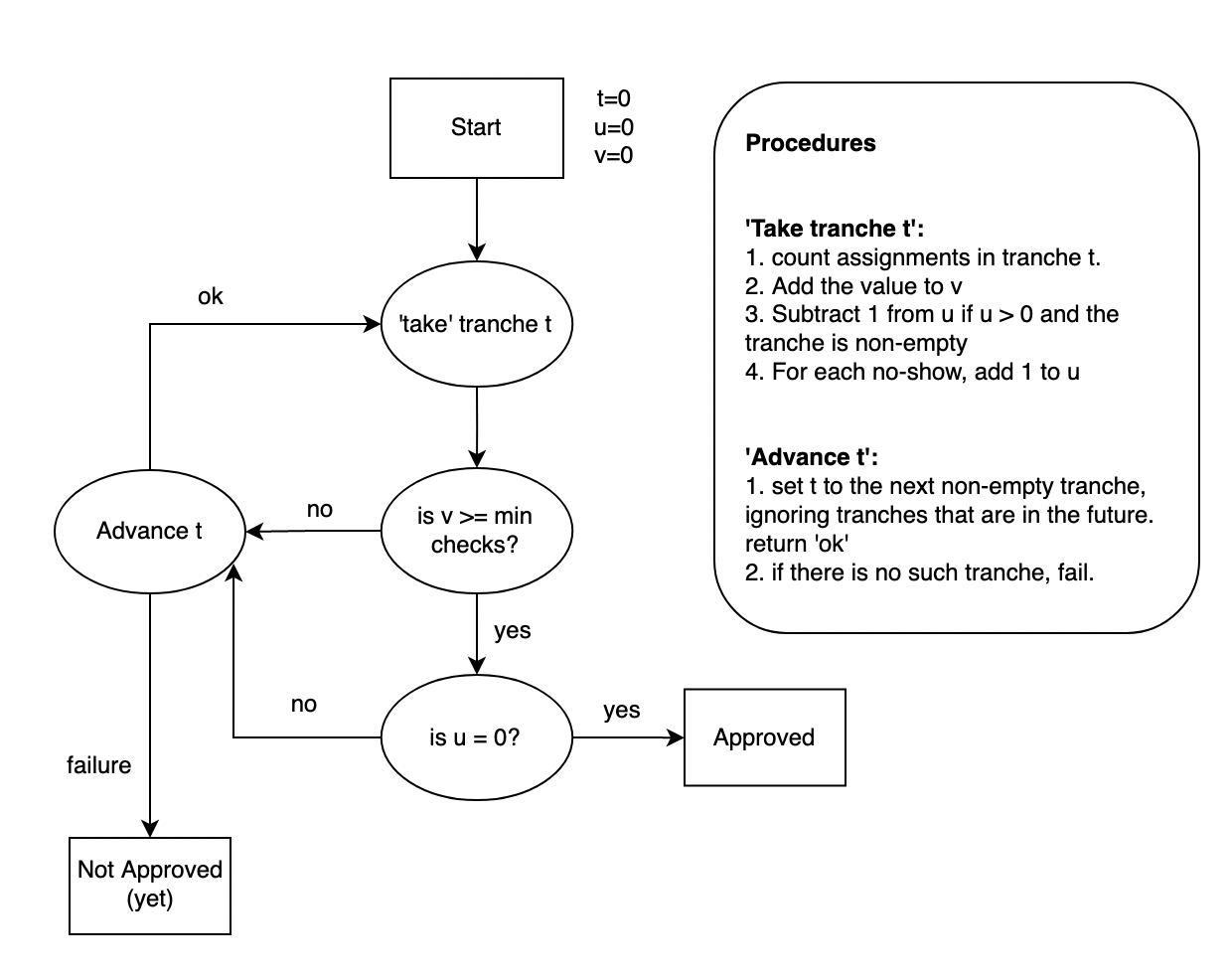

Determining how many tranches to take is done with the following procedure:

- Take tranches, starting with tranche 0, until they contain at least MIN_CHECKERS assignments.

- Take non-empty tranches, one for each no-show. If there are more no-shows in those non-empty tranches, repeat step 2.

- If all of the non no-show assignments are fulfilled, then the parachain block is approved. Put another way, if any of the assignments are still pending, then the parachain block is not approved.

If at any point you run out of tranches to take (the maximum is a protocol parameter), the block is not approved. In the real version of this protocol, there are some further constraints with respect to not taking tranches that are 'in the future' as well as drifting time based on each iteration of step 2.

This flow-chart captures the logic that each validator runs to determine if a parachain block is approved. It's important to note that this is only based on the assignments and approvals that the validator has actually seen. Assignments might exist that change the result of the counting procedure, but if they haven't been received by the validator running the procedure then they can't be considered.

How to count and interpret received assignments and approvals

The key takeaways from this procedure are that assignments for later tranches don't get counted at all if there are enough early assignments and that nodes that disappear under mysterious circumstances get replaced.

Here are 4 examples of results of the approval-counting procedure:

Whenever a validator runs this approval counting procedure and discovers that more assignments are needed, it checks to see whether it should trigger its own assignment and begin checking. The validator triggers its assignment if:

- The validator has not already triggered its assignment.

- The assignment's tranche is relevant to the state: either it is part of a tranche the state already accounts for or the counting procedure ran out of tranches and the assignment is not in the future.

In summary

The approval checking protocol is the primary fraud-detection mechanism of Polkadot. Before anything reaches this stage, we've ensured that the data necessary to check is available. This mechanism either results in the approval or escalation of every parachain block, and has been designed so a DoS attacker attempting to eliminate validators who check are replaced by even more checkers. Approval checking is the Hydra. It's designed to eat attackers and spit them out at the other end. Where it sends them to is a system we call disputes: Polkadot's Consensus Court of Law.

Disputes: arguing for money

A dispute occurs when 2 or more validators disagree on the validity of a parachain block. While the bulk of the prior content of this article is focused on the happy path, that is the case where a parachain block is actually good, disputes are about the error path where an approval checker actually detects that an invalid parachain block has become available.

The disputes process is relatively straightforward. It was designed to meet the following goals:

- Determine whether the parachain block is good or bad by putting it to a vote of all validators.

- If the parachain block is bad, make sure not to finalize or build upon any relay-chain block making it available.

- Ensure that the losers of the dispute are punished accordingly.

Primarily, disputes are about meeting one of the higher-level goals of Polkadot: make sure that nothing bad ever gets finalized.

Validators participating in a dispute cast votes in either a 'for' or 'against' category. Participation is either automatic or explicit.

Participation is automatic through backing and approval checking. When a validator has issued a backing attestation or an approval message for a parachain block, they automatically count as having participated in the 'for' category. In fact, honest validators keep a record of all recent backing and approval checking messages they've received in order to present evidence against their peers later on.

The vast majority of validators are not automatic participants. These validators participate explicitly, which means that they sign a vote for the 'for' or 'against' category. They do so after doing the same checks that an approval checker does, namely,

- Downloading the PoV data.

- Validating the state transition

- Validating the commitments to outputs of the state transition

Participation is not mandatory, but a dispute cannot resolve until at least 2/3 of validators have cast a vote in one side. Validators are rewarded for participation and are rewarded for being on the majority side.

Disputes either end in a for or against state because validation is deterministic. Previous Backing and Approval statements (labeled as (B) and (A) respectively) automatically get counted in the ‘for’ column.

There are slashing penalties for the losers of a dispute. Disputing a parachain block that is actually valid is just a waste of time and bandwidth so there's a small penalty for that. Submitting an invalid parachain block is an attack against Polkadot, so the slashing penalty is 100%.

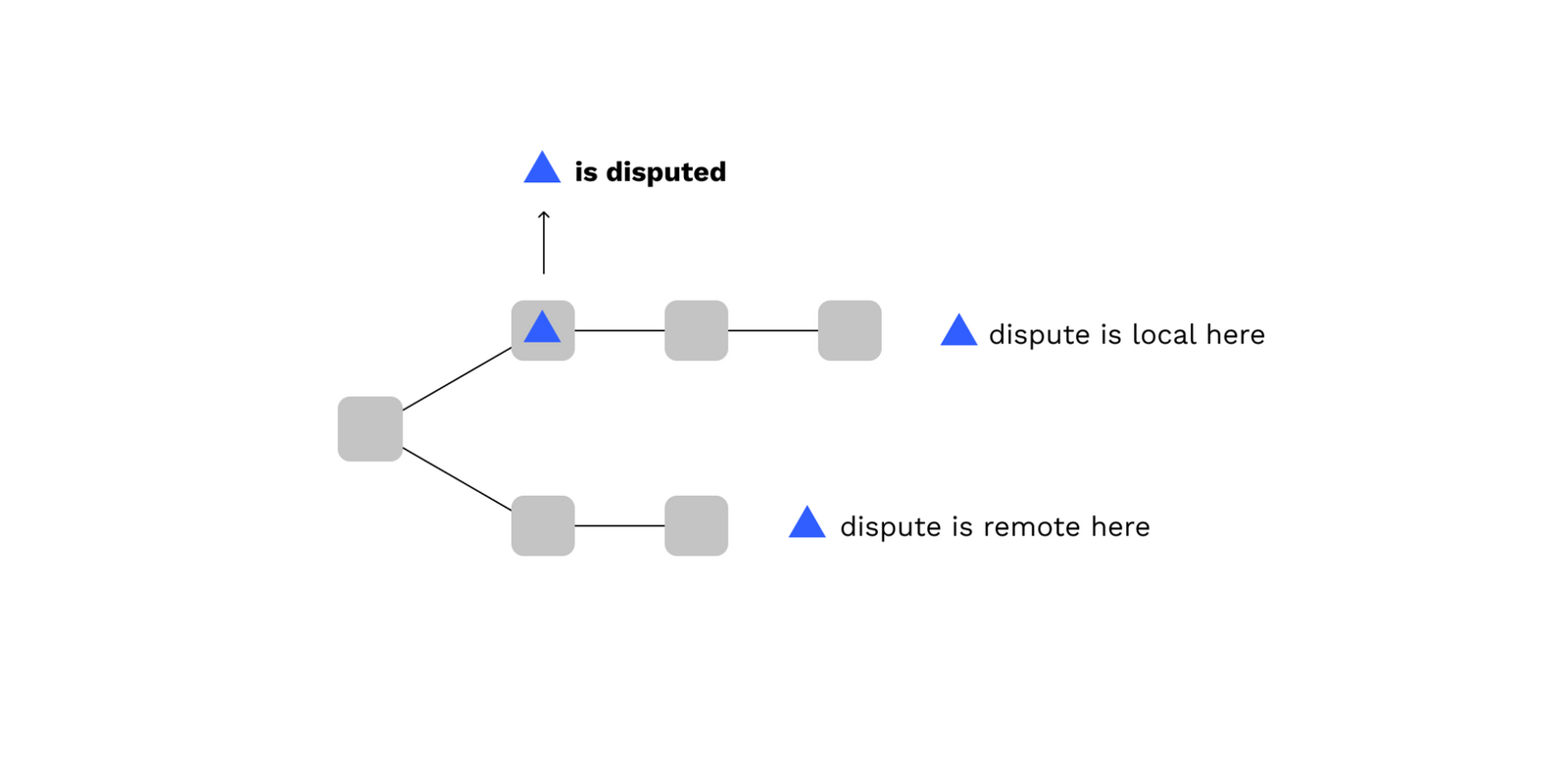

Remote and local disputes

Disputes are primarily an off-chain process. That is, they occur at the level of 'the chains' and not at the level of 'the chain'. However, the fork of the relay chain that eventually gets finalized should contain a record of the dispute. This is because slashing is an on-chain process.

When a dispute occurs, all votes are recorded on every fork of the chain in order to trigger slashing and create a permanent record of the dispute.

A remote dispute, with respect to a fork of the relay chain, is one which references a parachain block that was not included in this fork of the relay chain.

A local dispute, with respect to a fork of the relay chain, is one which references a parachain block that was included in this fork of the relay chain.

The reason this decision was made is because it informs us which forks of the relay chain need to be abandoned. Any relay-chain fork that records a local dispute which concludes against the parachain block should be avoided and not preserved by honest validators. In other words, honest validators observing that a parachain block is bad will automatically initiate a 51% attack against the forks of the relay chain that contain the bad parachain block.

The end result is that the finalized fork of the relay chain does not contain any parachain blocks that have lost disputes. However, when honest validators build the new chain and omit the bad parachain block, they replay the dispute on the new fork as a remote dispute. The punishment is preserved, but the effects of the crime are erased from history.

This diagram shows how a disputed parachain block is either remote or local based on which fork of the relay chain you're looking at:

A dispute is either local or remote with respect to a relay-chain block

Disputes and Consensus Rules

As with approval checking, disputes come with modifications to the consensus participation rules for honest validators. These changes have 2 main goals:

- To avoid finalizing any fork of the relay chain which refers to a bad parachain block.

- To avoid building on any fork of the relay chain which refers to a bad parachain block.

These goals correspond to changes in behavior within GRANDPA and BABE, respectively.

The GRANDPA voting rule is a modification of the approval-checking GRANDPA voting rule. It states:

Choose a block according to the approval-checking voting rule

Find the highest block B in that chain such that all blocks from the last finalized block and up to B only triggers inclusion for parachain blocks that do not have ongoing disputes or have lost disputes.

This is framed similarly to the approval-checking voting rule, but let's unpack the most important parts, which have validators ignore relay-chain blocks triggering inclusion for parachain blocks:

- that do not have ongoing disputes: This instructs validators to avoid finalizing parachain blocks that are under contention until enough validators have participated. In other words, 'better safe than sorry'.

- that have lost disputes: If a validator sees that 2/3 opinion against a parachain block, that validator will never vote to finalize a relay-chain block triggering inclusion for that parachain block.

In this diagram, we show some examples of how the disputes GRANDPA voting rule would be applied to a chain:

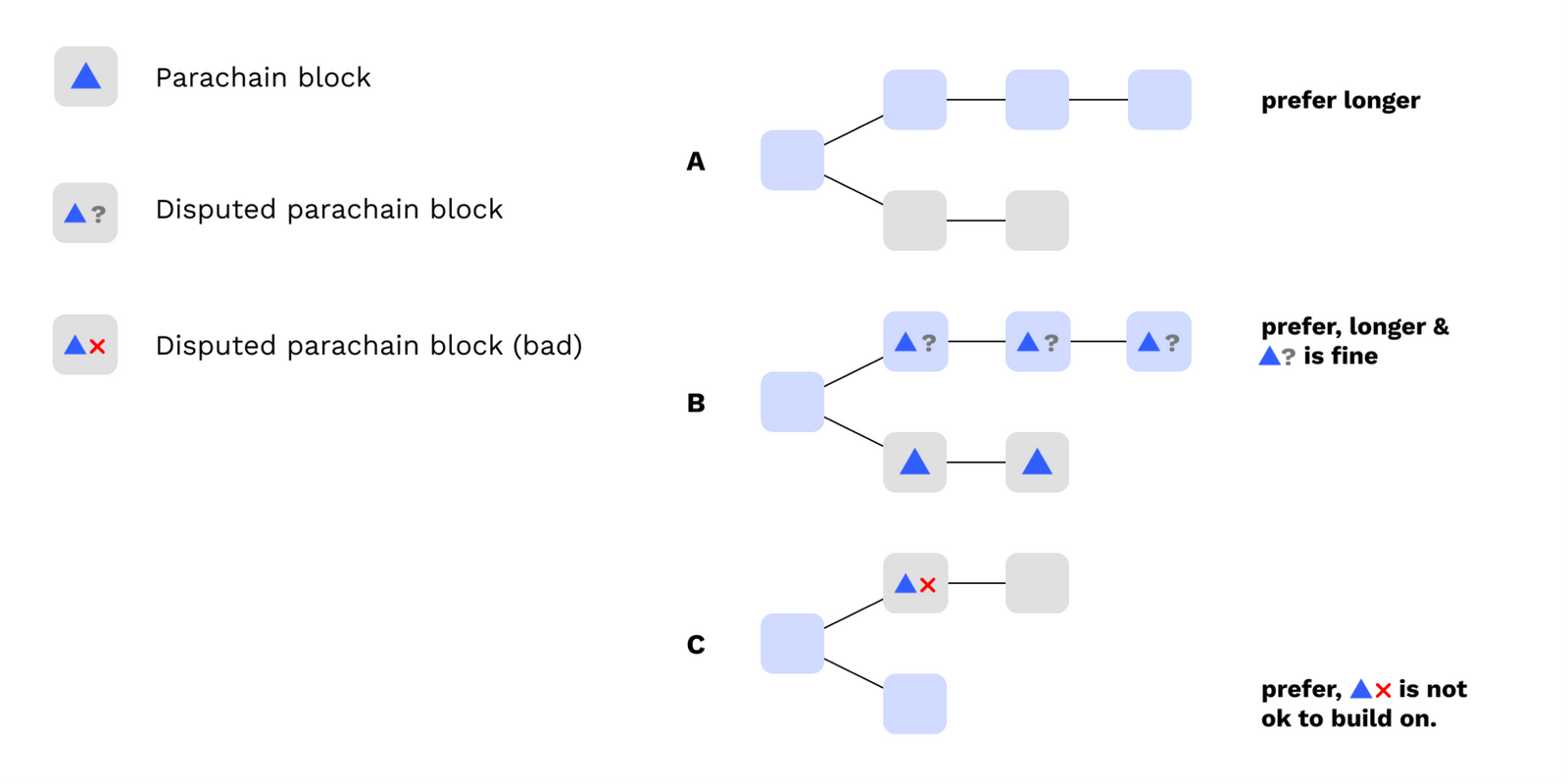

There's also a BABE (block authorship) chain-selection rule which serves the second goal. Normally, BABE instructs validators to extend the relay chain by building on top of the relay-chain block that has the highest weight, which is analogous to height. The modified BABE chain-selection rule states:

- Relay-chain blocks are considered viable either if they are finalized or if their parent block is viable and every parachain block the relay-chain block triggers inclusion for is undisputed or has won a dispute.

- A relay-chain block is a viable leaf if it has no viable children

- Validators should build on the viable leaf with the highest weight they're aware of.

The implication of the BABE chain-selection rule is that honest validators will abandon forks of the relay chain that trigger inclusion for any parachain blocks that are found to be invalid, even if that means temporarily building on a shorter chain.

The diagram below shows examples of how the BABE chain-selection rule requires validators to abandon and stop building upon chains that contain parachain blocks which have lost disputes. This effectively makes them 51% attack the bad branch of the relay chain.

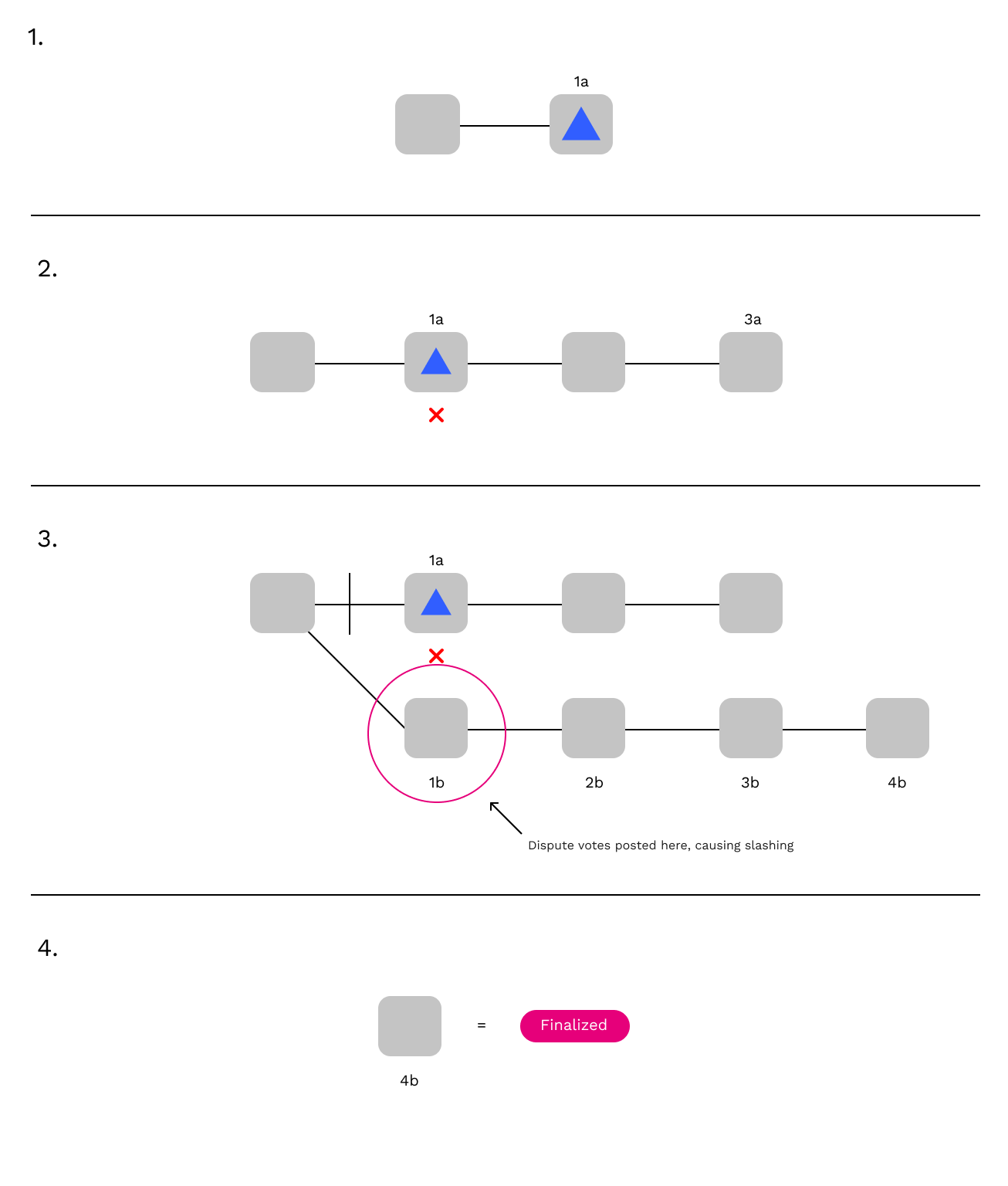

What that looks like in practice is a short and automated roll-back of the relay chain. Here's an example:

- In block 1a, a parachain block P is included.

- By the time block 3a is built, the parachain block P has been disputed and found to be invalid.

- Honest validators start ignoring block 1a and any children of 1a. Instead, they build a new chain starting with an alternate block 1b which doesn't include the invalid parachain block P.

- These honest validators post the dispute messages relating to parachain block P to the new fork of the relay chain, which ensures that the backers of P are slashed. Once 4b is built, it surpasses the original chain and 1b is finalized.

The rollback is possible because honest validators do not finalize 1a until it's approved, and the approval process is what raised the dispute. Once P is disputed, validators put the finalization of 1a on hold. When P loses the dispute, validators will refuse to finalize 1a under any circumstances.

Illustrated example of a ‘reversion’ where a bad parachain block is ignored

To sum up, the disputes logic is a means of ensuring that detected misbehavior is punished soundly and that the relay chain re-organizes to completely avoid the bad parachain block. Disputes and the associated chain-selection rules are the main things that differentiate Polkadot from a regular optimistic rollup. Optimistic rollups are running on top of a chain over which they have no influence on finality or fork-choice, which means that they have to be extremely conservative about the risk of finalizing any block that is bad and therefore impose long fraud periods and withdrawal durations (days or weeks).

In Polkadot, the disputes protocol and the chain-selection rules mean that finality is simply delayed a few seconds when a dispute is on-going and the chain can build around the bad block. Finality is still fast, and finality is still safe.

All together

This post has been a deep primer in blockchain consensus and how we've applied those concepts to build Polkadot altogether. A big part of our design methodology has revolved around making sure things work quickly when network conditions are good but correctly when network conditions are bad. Most of the time, there will be no attacking validators. Network latencies will be low, and bandwidth will be high. In conditions like these, approval and finality can occur in a few seconds. But when there are attacking validators or network conditions are poor, finality will slow down correspondingly and the relay chain has the power to reorganize around bad parachain blocks.

We've been working on this set of protocols, in one form or another since the summer of 2016. It's incredibly rewarding to see these things implemented and running on live, highly decentralized networks.

The blockchain scaling problem has only worsened since we embarked on this journey several years ago. We've seen a number of approaches, but many of them are lacking in either security or decentralization. Polkadot, through its backing, availability, approval checking, and disputes systems, is a practical solution providing scalability, decentralization, and security.

On protocol development

(Personal opinions follow)

Building software systems is a constant wrestling match between ideals, pragmatism, aesthetics, and time. Reality never quite matches the ideal. Nothing is ever perfect, but things can be good.

There is a disconnect between the idealized version of a protocol and the implementations that eventually run on computers. It's similar to the difference between a character in a play and the embodiment of that character by an actor. Servers worldwide will wear the costume of our validators, but they will never become the Validators of our protocol, no matter how hard they try.

Protocol development is a major undertaking. It requires significant time, energy, and focus. It requires a willingness to ignore the vast majority of the things that are happening at the fringes. These sacrifices are archetypal — a work can only be created by the offering of all that it is not. Building something is about orienting symbols in relation to each other. Most importantly, building requires a willingness to fail in doing so. As protocol developers, we have no choice but to fail. But in doing so we encounter the absurd, and find meaning.

The mass media of the internet encourage messages of building primarily as a means to an end. We're encouraged to build as a part of something greater: business, financial systems, social movements, and political statements. It's important to ground these aims in craftsmanship and the simple joy of having built something not just functional, but imbued with care and elegance. The effort to construct each piece of a system to be in alignment with the others is a source of pride, and is worthwhile even at the cost of other material rewards.

We've been building the protocols described here for over 5 years, and I chose to end this post this way to answer the question many readers will have: "Why would anyone spend 5 years doing this?". This is a message to all new joiners in the crypto space. This is for everyone who's been riding the waves since the surges of 2020. If you find yourself seeking a sanctuary from the greed and the fray, it exists, and it's been here the whole time.

source:https://polkadot.network/blog/polkadot-v1-0-sharding-and-economic-security/

Web3News

Web3News